As I write this article from Boston (where the snow has covered the grass in front of my school and apartment for weeks), I wish that I could easily transport some of this snow to parts of the country that need it. Other parts of the west, particularly in California are facing some of the worst drought conditions ever recorded. As Rod Smith pointed out in his Post earlier this week, the California State Water Project has announced a zero percent allocation, casting serious doubt over the reliability of one of California’s most important water resources. In times like these where there is much more demand for water than supply, what groups should receive water?

Well, the answer to that depends on whom you ask. In the midst of this debate, interest groups in California and across the Western United States have rallied to put a stop to hydraulic fracturing or “fracking” in areas that face extreme droughts. These groups argue that even barring the environmental concerns that fracking could cause, giving water to drilling companies in times of drought will put even further strains on our water resources in these drought stricken areas. In this piece I will discuss both sides of the issue, and address whether the potential positives of fracking can outweigh the negative ramifications of over-using water resources in times of drought.

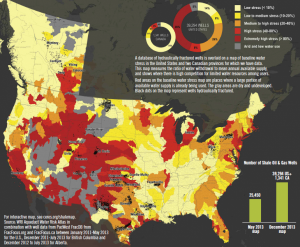

The process of fracking can provide the United States with a dependable, domestically-produced energy supply. However, the technique of removing the gas from shale formations takes massive amounts of water. Depending on the geology, a single well can use up to 5 million gallons of water to begin production. That amount of water may not be as consequential in an area that has abundant water resources. Unfortunately, some areas of the US where fracking is prevalent also are experiencing extreme drought conditions. As you can see in the map below, in places like Texas and Colorado, fracking operations are prevalent. However, these areas are also facing severe stresses on their water resources. As such, the debate over the process of fracking and the water resources it consumes has intensified.

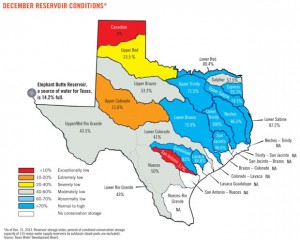

Whenever there is a drought, there are always discussions about who should receive water. In some cases in the west, citizens are questioning whether fracking is an appropriate use of scarce water resources. Texas is at the center of this debate. The Eagle Ford Shale and the Permian Basin in Texas produce some of the most productive natural gas wells in the US. But some are concerned that the water resources in the state, already under duress, cannot keep up with the growth in fracking. A recent report from Ceres, a sustainability advocacy group, compiled the amount of water that Texas uses for fracking. According to the study, 87% of the natural gas wells drilled in the Permian Basin of West Texas are in areas of high or extremely high water stress areas. The amount of water that drillers are demanding also is not dropping. According to a February 18th article in the Texas Tribune, water demands from drillers continue to rise despite the state’s crimped water resources. In McMullen County for example, drillers in 2012 used more water for fracking than the entire county used in 2011. If drilling continues at this pace in areas with high water stress, one can question how sustainable this practice is.

The debate over the sustainability of fracking is not limited to Texas. Colorado has seen a sharp increase in natural gas drilling over the last five years. A February 19th article in the LA Times states that the City of Greeley, Colorado sold drillers 207 million gallons of water in 2007. In 2012, that amount expanded to 513 million gallons. Farmers and property owners in the area are concerned that the high prices that gas drillers are willing to pay will drive local farmers out of business because they will not be able to pay nearly that amount for water. Colorado, much like Texas also faces drought conditions, and the state will have to make some tough choices on the future of drilling in the state. A new ballot initiative called Local Control Colorado is gathering signatures to get onto the statewide ballot in November. The initiative if passed would give local governments authority to limit hydraulic fracturing within their jurisdictions. Groups in Texas and California are trying to institute similar fracking moratoria.

As I mentioned in my first blog post on fracking, the issue is a sensitive one, and both sides of the argument have very strong opinions on the subject. The bottom line is that during times of drought, everyone feels the effects of constricted water supplies more acutely, and it is easy to point the finger at drillers as the main cause of the problem. But I don’t believe that the answer is as clear cut as what some anti-fracking groups are advocating. I do believe that drilling companies have not done a good job of addressing the environmental issues surrounding the process of fracking (I will address this issue in more detail in my next post). I also believe that we must review any water users’ consumption figures during times of drought to determine if it is the best use of a scarce resource. Certainly, the figures in Texas and Colorado show that drillers’ water demands are rapidly increasing. However, if you look at Colorado’s overall water usage, agricultural water use dwarfs what drillers use in the state. The same LA Times article I quoted earlier states that agriculture uses about 85% of the state’s water per year. Drilling uses about 2% of the water demands. Also, companies like Apache are looking to use recycled wastewater to pump into wells and begin production. But if we are going to make a dent in the water usage in the state, all parties, including agriculture and drilling interests have to find ways to conserve more water.

Hydraulic fracturing is a sensitive topic on its own. When you add in the politics of water to the equation, it is easy to understand why people on both sides feel so passionately about the issue. But before we draw conclusions about the industry, it is vitally important to remember that water conservation is everyone’s responsibility. Finding smart ways to reduce everyone’s water usage in times of drought is the only way to achieve sustainable water usage.

Oil drilling also results in tapping deep subterranean water and bringing it to the surface that would otherwise be inaccessible for human use. It is not unlikely that the deep water brought to the surface is equal to or greater than the 2% of surface water used by fracking.