Forecasters now believe that there is a 95% probability of El Niño conditions this winter, and the current strength of the conditions is one of the highest on record. California and other parched areas of the West hope that soaking rains will bring much needed relief to the drought conditions that have persisted for years. But will this potential series of monster storms this winter reverse the years of drought conditions California and much of the West has experienced? Unfortunately, the answer is likely no. Golden Gate Weather Services meteorologist Jan Null estimates that the rainfall deficit from the last four years of drought in California is approximately 68 trillion gallons. Even if we could capture most of the water that falls during the heavy storms, forecasters estimate it would take between 160% and 198% of average rainfall totals just to get us out of drought conditions. However, as the case of Texas shows this year, it takes more than a deluge to reverse the effects of drought over the long-term. Texas received a deluge of rain this spring to reverse a severe four year drought, only to re-enter drought conditions this fall. In this post, I will look at Texas’s and South Carolina’s trip in and out of drought conditions, and the potential lessons we can learn to prepare for the potential extreme rains California could see this winter.

A round-trip in Texas

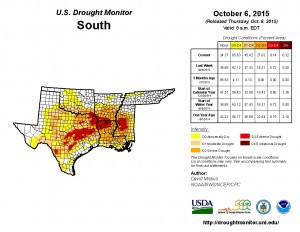

If one part of the country can show the potential negative effects of both drought and flooding, all within quick succession, it is Texas. The State of Texas has been on a roller coaster ride of drought, relief and the return of drought, all in less than a year. Just in June, I wrote a post about how a series of powerful storms brought a deluge of rain and erased the drought that had been plaguing the Lone Star State for almost five years. Unfortunately, the relief from the drought there was temporary. Just three months ago, just 4.63% of the state was under some form of drought, and the most severe rating at the time was moderate drought, covering just .25% of the state. But fast-forward to today, and the picture is much different. The most recent US Drought Monitor shows that 70.3% of Texas is under some form of drought, and 10.2% of the state is experiencing extreme drought. Areas of Oklahoma, Arkansas and Mississippi have areas of extreme drought; in northern Louisiana, exceptional drought covers 3% of the state. Both Texas and the recent flooding in South Carolina show the unfortunate negative effects of the both drought and flooding, and how much rain it takes to reverse serious long-term drought conditions.

Lessons from South Carolina

South Carolina is another good example of how quickly major storms can erase drought conditions, but the cost that comes with these huge storms. In early October, the US Drought Monitor reported that 73.2% of the state experienced drought conditions, and 10.9% of the state had extreme drought conditions. The deluge from a storm associated with Hurricane Joaquin brought days straight of heavy rainfall, and widespread flooding. In one week, the drought conditions in South Carolina dropped from 73.2% to 4.1%. Only moderate drought and abnormally dry conditions cover a small corner of the southwest part of the state.

Initial reports form South Carolina show that the state received record-breaking rainfalls over a very short period of time. The National Center for Environmental Prediction reported that from 8 AM on October 1st to 10 PM on October 5th, 26.88” of rain fell in Mount Pleasant. Ten other towns and cities in the state reported rainfall totals over 20” during the same time period. WeatherBell Meteorologist Ryan Maue estimated that 11 trillion gallons of water fell on the Carolinas during this storm, enough water to fill one-third of Lake Tahoe or filling the Rose Bowl 130,370 times!

While the storms did relieve the drought across South Carolina, it came at a high and tragic cost. Seventeen people died in South Carolina and two in North Carolina. Initial estimates of damage in South Carolina alone are around $1 billion. The office of SC Governor Nikki Haley listed some staggering statistics about the toll the storm put on the state:

- 40,000 households had no running water, 26,000 had no electricity as of Monday, October 5th.

- State highway patrol officers have responded to 4,926 service calls over the last several days.

- 2,122 of those calls have been responses to vehicle collisions.

- There are 3,000 National Guardsman in the state, and that number would increase to 5,000 Haley said Wednesday, October 7th.

- 600 people and hundreds of pets had been rescued.

- 824 people were in shelters as of Wednesday the 7th.

- 13 dams had failed, and 62 were being monitored.

- 74 miles of interstate highway were closed as of Tuesday the 6th.

For California, it matters where and in what form the rain falls

So what can California learn from the challenges Texas and South Carolina faced this year? First, while we may long for drought relief, storms and rains like the type Texas and South Carolina saw this year can cause significant damage and tragic loss of life. In both states, the economic damages associated with the storms topped $1 billion. In the 1997-98 El Niño, 17 people in California died and then-President Bill Clinton declared almost half of California a federal disaster area. Second, it matters greatly to California both where and how the precipitation falls. While the water conditions in the Pacific are showing some of the strongest El Niño conditions in modern history, the warming water is only one of the many things that have to come together for California to see the fruits of above average rainfall. Other weather patterns, such as the “ridiculously resilient ridge” (a ridge of high pressure over much of the Western United States that steered many storms around California, keeping us warm and dry for the last few winters) appear to be breaking down. But weather forecasters believe that the rains may be heaviest in Southern California, and this may not bode as well for reducing drought.

If the storms this winter largely miss Northern California, or fall mostly as rain rather than snow, the El Niño conditions may not help as much as people hope. The Merced Sun-Star reports that while forecasters are confident that Southern California will receive significant amounts of rain, they are less confident that Northern California and the Central Valley will receive the same soaking. Our major reservoirs are in in the north, including Lake Oroville and Lake Shasta, two of the largest reservoirs in the state. Unfortunately, the most recent reservoir conditions in these key areas show some of the lowest ever recorded levels. Lake Oroville and Lake Shasta are at 30% and 34% capacity respectively (for some stunning images of the current conditions in both of these reservoirs, click here and here). California will have to see significant precipitation in Northern California to put a dent into the prolonged drought.

More importantly, how the precipitation falls is key to solving the drought. California’s most important reservoir is the snowpack in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The snow gradually melts as the weather gets warmer and slowly releases water into rivers and streams for both humans and wildlife to use. This drought was so devastating because for the last two winters (and especially this last winter), the snowpack was virtually non-existent. Without much of the precipitation falling as snow, our state’s system of reservoirs will not be able to capture as much of the precipitation as is necessary to help alleviate the drought. So while it is encouraging that an El Niño event may trigger rains this winter, there are still many variables that will have to line up for California to see significant relief from the drought conditions that plague California.