Harvard’s Continuing Education in California Groundwater Rights

On January 22nd, Reuters posted an article “Harvard Buys Water Rights in Drought-Hit Wine Country.” An email flurry broke out with seemingly everyone in my contact list sharing a link. The article reported that the Harvard Endowment “has quietly become one of the biggest grape growers in California’s drought-stricken Paso Robles wine region, securing water well drilling permits to feed its vineyards days before lawmakers banned new pumping.” According to Reuters, a wholly-owned subsidiary of the $36 billion Harvard Endowment Fund has spent more than $60 million to acquire 10,000 acres in Santa Barbara County and San Luis Obispo County since 2012. Harvard’s entity now numbers among the top 20 wine growers in Paso Robles.

Reuters asks was Harvard’s move a “well-timed water play”? Is it? Nope. Instead, it is covering itself from investing in vineyards in a region with a rapidly increasing groundwater overdraft problem.

A Personal Digression

Every summer since 1999, I have driven from Southern California through Paso Robles to the Carter Cup Classic at Pebble Beach. Taking Interstate 5 to State Highway 46, I drive through the beautiful Paso Robles area. As a Hydrowonk, I knew about the groundwater challenges in the region. As an economist, each year (as more vineyards were planted) I kept asking myself how the millions of dollars invested to bring vineyards to maturity in the area “penciled” in the face of unregulated groundwater pumping in a basin marching to and beyond overdraft.

SLO Becoming Vineyard Country

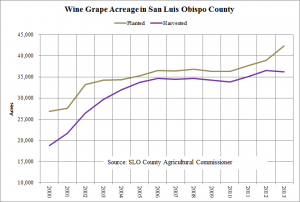

San Luis Obispo County is indeed becoming “vineyard country” (see chart). The planted wine grape acreage increased from 26,800 acres in 2000 to 42,320 acres by 2013 (last year of available data). Acreage harvested increased from 18,801 acres in 2000 to 36,248 acres in 2013. (Note: there is a gestation period between the planting of vineyards and commercial production). There is a recent “investment boom”, where the acreage harvested has been relatively flat while the acreage planted has jumped by 6,000 acres since 2010.

With groundwater overdraft on the foreseeable horizon during this expansion and vineyards a long-lived capital asset, what gives? Who is doing the due diligence? What do they know? What am I missing?

Paso Robles Basin in Disarray

The expansion of groundwater pumping (driven by expanding vineyard acreage) generated a sharp decline in well levels, including the drying up of shallow domestic wells. Before 2013 when the county halted new drilling, the basin was governed by the rule of capture—landowners could pump groundwater for use on overlying lands. Was groundwater pumping expanding in the face of an emerging overdraft an instance of a “race to the pump house”? That is, were vineyards establishing a “historical baseline” that would be used to establish larger pumping rights either through adjudication or local groundwater regulation?

By 2013, the San Luis Obispo Board of Supervisors imposed a ban on new pumping. Harvard secured permits to drill seven 800 foot wells six days before the ban went into effect. Recently, Harvard acquired rights to drill 16 new wells between 700 feet and 900 feet—evidently the event that triggered Reuter’s story. The stated premise was pumping from deeper wells will not interfere with the shallower domestic wells.

Observations

A well permit is not a water right. The Reuter’s story confuses the two. Until a recently formed local district adopts groundwater regulation, the jury will be out on what “water rights” a newly drilled well secures. There may be significant slippage of water from the cup to one’s mouth.

At the same time, drilling wells may be the “ticket” to allowed pumping. For example, it has been common in groundwater adjudications to allocate rights to pumping on the basis of pumping in a “pre-lawsuit” historic period. However, the Antelope Valley Groundwater Cases are addressing the fact that groundwater rights are based on landownership that cannot be lost from non-use. Reliance on historic use may not totally govern.

Drilling wells to deeper depths than residential wells need not mean that new pumping from deeper wells do not impact shallower residential wells. “Geology matters.” “Going deep” only helps if one is penetrating a different geologic formation that has limited (or, better yet, no) communication with the formation tapped by shallower wells.

Reuters compared the price of irrigable land “in the heart of the Paso Robles region” (running at $15,000/acre to $20,000/acre) to the price of dry pasture (running at $3,000/acre) as an indicator of the value of water. This differential is more about the capital investment in vineyards than about the value of water rights. Under the rule of capture, all lands have a right to pump groundwater for use on overlying lands. Lands planted in vineyards have soil characteristics suitable for wine grapes and an accessible groundwater supply (we are back to geology). Dry pasture lands are best suited for, you guessed it, dry pasture. The current asking price for undeveloped agricultural lands in Paso Robles is about $7,500 per acre. Therefore, the prices cited by Reuters ($15,000/acre to $20,000/acre) are probably for developed agricultural lands.

Final Thoughts

Harvard’s acquisition of well permits was more about “covering” itself during the transition from the rule of capture to regulated groundwater pumping than a “well-timed water play.” A true “water play” in Paso Robles would have anticipated the groundwater overdraft and get ahead of the curve with a solution—which would have been pre-emptive groundwater adjudication.

Instead, we observe significant expansion of investment in vineyards, declining water tables, drying-up of domestic wells and the imposition of a ban on new well drilling. Relative to the Central Valley, the geographic scope of the lovely Paso Robles basin is small and the number of pumpers far more limited in number. Why didn’t the capital market see the virtue of developing groundwater management institutions in tandem with their millions invested in vineyards?

A few years ago, Hydrowonk learned that proponents of the local water district argued that development of supplemental water supplies was the solution to Paso Robles groundwater challenges. Supplemental supplies, of course, are a useful tool in groundwater management. The mantra a few years ago was importing water from the Central Valley. How does that idea look today?

The Paso Robles basin will be a showcase, for better or for worse, of the transition from the rule of capture to groundwater management in California. With the prospect of supplemental water supplies imported from the Central Valley looking quite “speculative”, allowed pumping will be limited to safe yield. Arm wrestling anyone?

An interesting and timely piece, Rod. It seems like this issue is gaining momentum in a lot of areas. Stanislaus County has discussed this issue for the last year or so. You mentioned Antelope Valley which is in the midst of a decade+ adjudication. Where do you think the next hotbed of debate in the state on this issue will be?

Jeff:

Thanks for kind words. Hard to pick the “next area”, but Stanislaus County may be a good candidate with BOR not delivery water for groundwater replenishment.