This year’s Groundhog Day was symbolic in more ways than one. When Punxsutawney Phil emerged from his burrow on February 2nd, he did not see his shadow and predicted an early spring. In the Southwest US, his prediction has so far come true. Despite early hopes in January that the strong Pacific El Niño would help bring an end to the drought, February has so far been a bust. The National Weather Service reports that globally, January 2016 was the hottest on record and that temperatures across the Southwestern US reached records. In some parts of California and the desert Southwest, temperatures have been between 15 to 25 degrees hotter than average. As the temperatures have risen, precipitation amounts have fallen. While forecasters believe that the storms may return with some intensity in March, a ridge of high pressure has come into place that blocked storms from tracking through California and the Southwest US. These patterns are reminiscent of the El Niño predictions in 2014 and 2012 that never showed up. But unfortunately, much like Bill Murray’s character woke up to the same day over and over again, the California remains in the midst of exceptional drought conditions month after month.

El Niño predictions are extremely challenging, and the weather effects of the ocean warming depend on a host of atmospheric conditions. Everything from the ocean warming to the proper jet stream have to come into place at the right time for the Southwestern US to see an appreciable reduction in the drought. In the meantime, farmers, city planners and environmentalists are all waiting to see whether March will (hopefully) bring us the storms we need to at least make a dent in the drought conditions. But some environmental indicators are showing that parts of our ecosystem are suffering long-term stresses from the effects of drought and climate change. What are these indicators telling us and can the damage be reversed if the drought abates? I will address both of these issues in this post.

Fish Stocks

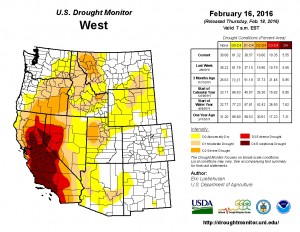

It always seems that somewhere in the Western United States faces some form of drought. The only differences are the intensity and location. Indeed, according to the US Drought Monitor, the Western region has always had some level of drought since the beginning of 2000. The intensities have ranged from a low of 15.38% of the area during the week of March 28, 2000 to the week of November 5, 2002 where 100% of the Western US had some form of drought. The most recent Drought Monitor shows that 61.32% of the Western US has some form of drought. While this figure is down from 77.23% at the start of the water year, parts of Montana, Idaho, Utah and Oregon still have severe drought. Nevada and California still have large areas of exceptional drought.

Against this drought backdrop, population growth and demands for water have continued to put strains on limited water supplies. The US Bureau of Reclamation’s data on the elevation of Lake Mead for example shows that that the Lake has fallen approximately 130 feet since the beginning of the century. (Lake Mead was at 1,214.26 feet in January 2000 and currently sits at 1,084.3 feet at the time of publishing.) The lower water levels have taken their toll on fish species across the Western US. One of the most controversial species in the Western US is the Delta Smelt, which lives only in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. The wild population of the species is on the verge of extinction as the drought drags into its fifth year and agricultural and municipal demands keep putting pressure on water supplies from Northern California. Mid-January trawls found only 4 male and 3 female wild smelt. The fall 2015 trawls found similarly low numbers of fish.

Other species of fish face similar fates. Scientists from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimate that only 3% of juvenile Sacramento River Chinook survived their migration to the sea in 2015. This figure follows another devastating year for the species where an estimated 5% of the juveniles made it to the ocean in 2014. The rivers in both of these years had too little water and was too hot for most of the juveniles to survive. The historically low fish counts for these endangered species has only turned up the heat on the “man vs. fish” debate over how to allocate limited water supplies.

On the one hand, environmental groups argue that we need to do even more to protect species that are on the brink of extinction. University of California-Davis biologist Peter Moyle, who has studied the Delta Smelt for decades said, “The probability of the Delta Smelt surviving in the next three years is relatively low. The chances of it bouncing back from where it is today seem very unlikely.” He argues that the Smelt are a “canary in the coal mine” and a good indicator of the overall health of the Delta ecosystem. If the Delta Smelt cannot survive there, other species further up the food chain may have troubles. Environmental groups point to the drought and water diversions out of the Delta as the main culprits of the demise of endangered species such as the smelt and salmon. They argue that slowing water diversions and keeping more water in the ecosystem will help to protect species that face the prospect of extinction.

On the other hand, agricultural and municipal water users argue that we are not prioritizing our water uses correctly when we leave significant quantities of water in rivers to save fish rather than diverting it. The State Water Contractors Association pointed out that in January alone, 225,000 acre-feet of water that could have been diverted was not because of pumping restrictions in the Delta to protect endangered species. Assembly Member Travis Allen (R – Huntington Beach) in an interview with Fox News said, “When we are diverting our water to save a couple of pinky-sized fish, and leaving hundreds of thousands of acres to lie fallow, there is something wrong with our priorities.” The debate over the highest and best use of water resources will likely continue to rage on as the drought now enters its fifth year.

The Health of our Forests

Fish stocks are not the only species showing signs of stress from prolonged drought. Forests in the Western United States are also dying as a result of limited rains. The US Forest Service estimates that in the Sierra Nevada Mountains alone, over 6 million trees may have died as a result of stress from the drought. Surveys of California’s Sequoia Kings Canyon National Park show that one percent of the giant sequoias studied have shed more than half of their leaves, a mechanism for them to cope with the drought. In the over 120 years of records that the Park Service has, there have been no reports of this phenomenon happening. The US Forest Service is concerned that the negative effects of climate change on the health of US forests will not be limited to the Western US. In a recent study entitled Effects of Drought on Forests and Rangelands in the United States, the authors argue that forests across the United States may not be able to adapt as quickly as the climate is changing. Forests can migrate and grow in new areas where the climate is more suitable (for example moving northward for a species that thrives in colder climates), but there are natural limits to how quickly this migration can happen. If the climate changes faster than forests can adapt, then forests across the country may be in danger of feeling the negative effects of climate change.

We are seeing the effects of climate change and prolonged drought in both fish stocks and the health of our forests. Regardless of your opinion of the policies associated with water allocation, attempting to protect species that the drought has affected have real and long-lasting implications. It seems inevitable that there will continue to be debate over the highest and best use of water for the various interests in the Western US. It is up to our policymakers and affected entities to make sensible policies to address the needs of both sides of the argument to minimize the disruptions the drought has on the environment and the communities that rely on water for business and daily life.