In my last post, I wrote about how Apple Valley, a community in San Bernardino County began an eminent domain proceeding to take over Apple Valley Ranchos Water Company (AVR), a private water utility in the town. At the time of the passage of the resolutions of necessity in November 2015, the town’s citizens seemed ready and willing to embark on a protracted process to gain local control over the water system. A poll that the town conducted around the time of the resolutions of necessity determined that 70% of the population supported a takeover of the water system. The continued cost increases, drought surcharges and the desire for local control seemed to unite the citizens around the need for eminent domain proceedings.

However, in the ensuing year, the sentiment towards the water system’s acquisition system has changed. During the 2016 presidential election, two ballot measures, Measures V and W were placed on the ballot. Each ballot measure placed restrictions on the amount of borrowing the Town Council could authorize without a vote of the people. Measure V would require voter approval before the town could issue more than $10 million in public debt. (The town estimated the water company’s appraised value at $50.3 million.) Measure W would require voter approval of $5 million or more in bonds but exempted the Apple Valley Ranchos acquisition. In the end, both measures received more than 50% approval, but Measure V received more total “yes” votes (17,707 votes and 14,789 votes were cast respectively for Measures V and W) and therefore became law.

After the passage of Measure V, the town will have to go to a vote of the people to issue bonds to purchase Apple Valley Ranchos if they receive approvals to condemn the water assets. The measure adds an extra layer of cost and uncertainty for the town to complete a successful takeover of AVR. What caused the citizens’ sentiment to shift over the last year? And what may be in store for the future of the town’s attempt to take over AVR by eminent domain? I will argue that a combination of rising costs associated with the acquisition and some old fashioned politics helped to change public sentiment towards the takeover.

It is not Cheap to Take Over a Water System by Eminent Domain

When an eminent domain proceeding begins, the jurisdiction attempting to take over the asset must pay for a host of services related to the acquisition. At the same time, if the owner of the asset has no interest in selling to the jurisdiction, they too will fight to keep retain private ownership. As such, bills associated with the eminent domain process can add up quickly, and this was the case in Apple Valley.

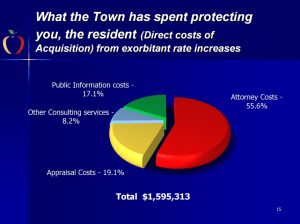

Starting in August 2015, Apple Valley began to release a quarterly series of transparency reports that outlined the taxpayer-funded costs associated with the town’s acquisition proceedings. According to the accounting report through August 31, 2016, the town spent $1,595,313 for legal and consulting services related to the acquisition. The town has budgeted $3,500,000 for the process, so they have already spent approximately 46% of their budgeted amount.

Where has the money been spent so far? (Click here for a detailed breakdown of costs and see the graphic below.) The majority of costs (55.6% or $806,755) have gone to attorney’s fees associated with the case. Included in this cost is $165,995 to fulfill 83 public records requests related to the takeover. Attorneys have also provided guidance on the acquisition, rate cases, and Apple Valley’s attempt to purchase AVR during the sale of Park Water to Liberty Utilities (see my last post for details of this). The town also budgeted $127,400 on the appraisal of the water system. Engineering and public relations consultants round out the spending. Initially, some of these contracts were signed confidentially, but the town released the details of them as an on-going effort to remain transparent.

The amount of money that Apple Valley is spending towards the effort is not unique. The City of Claremont is pursuing its own takeover bid of the private water utility that serves the city. According to the Inland Valley Daily Bulletin, Claremont spent $3.7 million prior to the trial which was heard this summer, and had another $1 million budgeted for the trial phase. However, the court dealt a serious blow to Claremont in November when Judge Richard Fruin preliminarily ruled in favor of Golden State Water and concluded that it was in the best interest of the public for the water company to remain as a privately-owned utility. In the ruling he said, “The court will dismiss the complaint because the city’s plans for operation of the Claremont water system do not provide adequate assurance that it will maintain water quality, safety and reliability in the Claremont service area at the level now provided by Golden State.” On December 9th, the court issued its final decision, again siding with Golden State Water and dismissing Claremont’s claim. Apple Valley is still waiting for its day in court. However, in the interim, local politics has also played a role in the eventual outcome of Apple Valley’s attempt to take over the water system

Apple Valley Measures V and W: Adding Another Layer of Complexity to the Takeover

As the court case played out in Claremont, Apple Valley also had some political changes that added another layer of complexity to the process of potentially taking over the water system. Hypothetically for both Claremont and Apple Valley, each municipality would have to issue debt to finance the purchase. There are a variety of ways that cities can finance such purchases; some methods require voter approval, some do not. In Claremont for example, the city staff in March 2014 asked for direction from the City Council as to how they would like to finance the acquisition. (For details on the financing options Claremont had at its disposal for the potential acquisition, click here to view the full staff report. The discussion of financing options begins on page 4.) Claremont ultimately decided to bring the financing measure before a vote of the people and put Measure W on the ballot in November 2014. Measure W passed with 71.98% of the vote and allowed Claremont to issue up to $135 million in water revenue bonds to pay for the acquisition of the Claremont water system.

Unfortunately for Apple Valley’s water acquisition efforts, the citizens there did not support the town’s attempt to exempt the AVR acquisition from a vote of the people. On the November 2016 ballot, two competing measures, Measure V and Measure W went before the town’s voters. Measure V began as a citizen-based initiative which Apple Valley residents Pat and Chuck Hanson authored and gathered 3,873 signatures by June 2016, enough to qualify for the November ballot. The measure would require a vote of the people for the issuance of any public debt over $10 million. Proponents of the initiative argued that the town had not been accountable to the taxpayers and not fiscally responsible by spending over $1 million towards the acquisition of AVR. Liberty Utilities, the parent company of AVR, also provided campaign donations to support Measure V.

In response, the Town Council on July 26th voted to place the competing Measure W on the November ballot. Measure W would require voter approval for any town debt greater than $5 million, but importantly it exempted the acquisition of AVR from this rule. (For the official ballot statements, click here for Measure V and here for Measure W.) From the outset, the town-sponsored Measure W faced a few challenges. First, Measure V was able to raise significantly more money to spend on the campaign. Initial campaign spending reports show that Liberty Utilities alone spent approximately $250,000 to support Measure V, while Measure W’s advocacy group H2OWN raised around $18,000. Further, municipalities have strict advocacy rules in place which only allow them to “educate” voters about ballot measures, but do not allow them to specifically recommend supporting or opposing a specific measure. When the city sent out a newsletter discussing the merits of Measure W, the town received criticism of bias and improper use of taxpayer funds to support its own measure. In the end, these obstacles were too challenging to overcome, and Measure V prevailed.

What is Next for Apple Valley?

While the City of Claremont determines the next steps after its defeat in LA Superior Court, Apple Valley’s case will move forward. If the courts reach the conclusion that Apple Valley may condemn the system, it will still have to put the bond issuance before the vote of the people per Measure V. Let me be clear – In this post, I am neither supporting nor opposing the eminent domain proceedings in these municipalities. Ultimately, it should be up to the people to decide whether the jurisdiction should move forward on condemnation proceedings. However, I also believe that the elected officials have an obligation to let the people know of the risks and costs associated with pursuing condemnation. As we saw in Claremont, there is no guarantee that the courts will decide in the city’s favor when the condemnation hearing is heard. Further, as both Claremont and Apple Valley showed, even getting the case to court is an expensive proposition. Apple Valley has spent $1.5 million already before the court trial; Claremont has spent close to $5 million and barring appeals, did not receive a positive outcome. The city will also be on the hook for Golden State Water Company’s legal fees. The citizens must be made aware of these costs and risks, because ultimately, they will be responsible for the bills associated with the attempted takeover.