The California Supreme Court can protect incentives for responsible groundwater management by agreeing to review an appellate court decision (Mojave Pistachios v. Indian Wells Valley Groundwater Agency) challenging Indian Wells Valley Groundwater Sustainability Plan (“GSP”). The dispute is over whether the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (“SGMA”) allows Indian Wells Valley to eviscerate a landowner’s (Mojave Pistachios LLC) groundwater rights without due process and impose unreasonable “fees” for a speculative GSP. The future of reasonable groundwater management hangs in the balance.

This dispute has garnered widespread interest from parties interested in groundwater rights and responsible groundwater management. Third parties supporting the challenge include the California Building Industry Association, Western Growers Association, California Farm Bureau Federation, American Pistachios Growers, Pacific Legal Foundation, Howard Jarvis Taxpayer Foundation, and individual landowners as far from Indian Wells Valley as Madera. Hydrowonk is unaware of any third parties intervening on behalf of Indian Wells Valley.

The California Constitution and common law require groundwater basins to be managed towards maximizing the reasonable and beneficial use of groundwater, without causing an undesirable result. SGMA codifies the definition of “sustainable yield” as the “maximum quantity of water, calculated over a base period representative of long-term conditions in the basin and including any temporary surplus, that can be withdrawn annually from a groundwater supply without causing an undesirable result.”

In Indian Wells Valley, the GSA utterly fails to consider any strategy to manage the Basin to maximize the beneficial use of groundwater. Instead, it intentionally focuses on the elimination of agriculture.

Principles of Responsible Groundwater Management

Hydrowonk has followed the development of adjudicated groundwater basins in California for more than four decades. This experience has revealed “rules” for effectively addressing groundwater overdraft.

-

- Understand the dimension of the challenge.

This inevitably involves working through alternative analyses on the nature, extent, and urgency of meeting the challenges of groundwater overdraft. “Dueling hydrologists” will provide alternative visions, although there are ways to separate “pepper from fly****.

-

- Define a system of pumping rights.

By its very nature, addressing groundwater overdraft requires reductions in pumping relative to historical levels after the use of any temporary surplus in a basin. A responsible system includes equitable treatment of existing groundwater rights. Overlying users have priority over appropriators (those who pump groundwater for use off their lands), subject to prescription. “Dueling lawyers” will advance alternative ways to balance competing rights.

In the end, adjudications involve proportionate reductions from a defined historical baseline, commonly with a “ramp down period” providing time for pumping to decline to long-term levels.

-

- Develop an action plan.

A Groundwater Sustainability Plan must, ironically, be a plan. Specific actions should address identified components of groundwater management. Given the inevitable variability in hydrologic conditions and the less than “perfect knowledge” of underlying science, monitoring actual circumstances on the ground should guide improving groundwater management strategies and accessing their effectiveness. Learning is inevitable and should guide refinements or even “rethinking” when the facts on the ground fly in the face of earlier conclusions, assumptions, presumptions, or wishes.

-

- Fees and Assessment Must Be Related to the Costs of the action plan.

Reasonable fees and assessments must be tied to a specific plan. Funding “aspirational” ideas not backed by substantive analysis of potential effectiveness doesn’t pass muster.

Indian Wells Valley Failure

Hydrowonk experienced first hard the arbitrary nature of Indian Wells Valley GSP when he was retained in 2021 by Mojave Pistachios LLC to comment on Indian Wells Valley then proposed plan and replenishment fees.

-

- Indian Wells Valley’s Replenishment Fee is Unreasonable.

The replenishment fee is to fund the first phase of Indian Wells Valley “Groundwater Augmentation Project” (the purchase cost estimated at $2,112 per acre foot over five years) and an associated Shallow Well Mitigation Project (estimated at $17.50 per acre foot until imported water supplies are delivered no later than 2035) for a total Replenishment fee of $2,130 per acre foot.

The Groundwater Augmentation Project is inchoate. There is a lack of a disciplined project plan. Rather than set by the funding requirements of a disciplined project plan, the replenishment fee is set to speculatively raise a financial reserve over five years to fund assumed water acquisitions, not yet identified, with the presumption that Indian Wells Valley will “figure out later” how the water will be delivered, at what cost, and whether there are purchasers of imported water.

The replenishment fee must be tethered to the funding requirements of an executed project’s development and finance plans. Standard commercial practice includes at least some evidence of the potential terms of water acquisitions and conveyance arrangements with specific parties. Project plans lay out the timing of critical tasks (such as definitive agreements for acquisition of water and conveyance, environmental review, regulatory approvals, financing arrangements, and necessary construction schedules) and the required funding to reach each identified milestone. Risk assessment identifies key risks and risk management strategies to manage identified risks as they materialize. A finance plan identifies reasonable and prudent fees to pay the project’s life cycle cost at the least cost to ratepayers over time, who have a demonstrated demand for future replenishment water.

None of these elements are part of the GSP. Rather than engage in responsible project development, Indian Wells Valley aspires to build a financial war chest without any concrete project or finance plans. Therefore, $2,112/AF of the proposed replenishment fee of $2,130/AF is unreasonable and ultimately imprudent.

-

- Replenishment Fee is Unprecedented.

Indian Wells Valley replenishment fee is an extreme outlier of replenishment fees levied in California. The Mojave River Adjudication fees are less than $700 per acre foot, tied to the actual cost of replenishment operations. The Antelope Valley Adjudication follows the same model, where the watermaster’s annual report includes Appendix O, “Financial Analysis of Replacement Water Assessment” showing how the rates are calculated from the cost of actual operations.

As required by Proposition 218, local agencies set replenishment fees based on the revenue requirements of actual operations that provide actual replenishment water. Replenishment fees are not set to fund financial war chests for future, hypothetical ventures.

-

- Replenishment Fee Renders Irrigated Agriculture Economically Unviable.

Mojave Pistachios LLC transformed 1,400 acres from alfalfa to pistachios before the California Legislature passed SGMA. The movement towards higher-valued agriculture has historically been advocated on long-term public policy grounds.

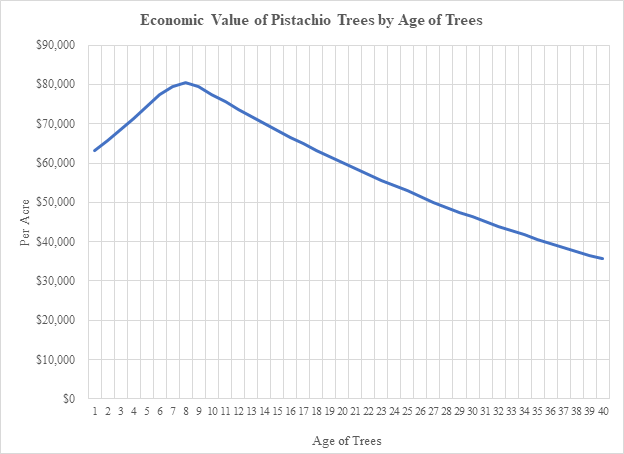

Permanent crops represent significant investment and patience. Pistachios take six years from the first year of planting before trees generate commercial yields that do not reach maturity until the ninth year. Lack of water places significant investment at risk. The economic value of pistachios trees increases until trees reach maturity and then decline with the age of trees. Using data from the UC Davis Department of Agricultural & Resource Economics 2015 “tree loss calculator” for pistachios in the South San Joaquin Valley, pistachio trees reach a peak economic value of $80,000 per acre by the ninth year (full maturity) and starts declining over time (see “Economic Value of Pistachio Trees by Age of Trees”).

Using UC Davis Crop Budgets, Hydrowonk calculated that the annual economic loss per acre foot of water is about $1,575/AF, 26% below the proposed replenishment fee. Therefore, faced with a $2,130/AF replenishment fee, the prudent economic decision is to shut down, abandon the orchard and convert land to the next best (inferior) economic use, which may be permanent abandonment.

Imposing unreasonably high replenishment fees renders any future irrigated agriculture in Indian Wells Valley even more economically unviable. Unlike the case of orchards already planted, where significant capital investments have been already made, new ventures face even lower anticipated future income when making investment decisions due to upfront capital investment including land acquisition costs, the cost of installing irrigation systems and other improvements, and the cost and delay in establishing commercially viable trees.

-

- Entire GSP Based on Economic Illiteracy.

Indian Wells Valley’s GSP is based on an unreasonable and unprecedented proposed replenishment fee that will destroy the economic viability of current and future irrigated agriculture in Indian Wells Valley. What is the explanation? Imprudent project development, inadequate economics, and economically flawed decision-making.

Prudent project development starts with a project plan, budget and schedule that includes securing the terms of necessary agreements with a plan for project financing. Indian Wells Valley has reversed the process. It seeks to set a replenishment fee presuming a demand for imported water from an undefined project including unspecified timing, amount of water and financial terms.

Given Hydrowonk’s experience in negotiating long-term agreements and acquisitions as well as conducting due diligence on water projects and investments, the GSP and proposed replenishment fee evidence undisciplined decision-making. On the one hand, the GSP contemplates a Groundwater Augmentation Plan to provide 5,000 AF per year of imported water “no later than 2035.” In the interim, the Shallow Well Mitigation Plan will mitigate the impact of pumping above the Basin’s sustainable yield. For groundwater users responsible for funding imported water, they pay replenishment fees today to fund an unknown project that may never materialize.

Indian Wells Valley planning has failed. It lacks concrete evidence of the ability and willingness of groundwater users to pay for imported water that would support the negotiation of actual transactions for water and conveyance. In effect, it wants the future users of imported water to pre-fund a project without a plan, including the estimated price tag for conveyance. Even worse, the GSP presumes that agriculture cannot pay the fee and that it will cease production. The intent of the GSP is to extinguish agricultural use. On June 14, 2024, Indian Wells Valley is moving to shutter wells for agricultural uses that cannot and have not paid the replenishment fee. Many have already left the valley.

-

- GSP Lacks a Finance Plan

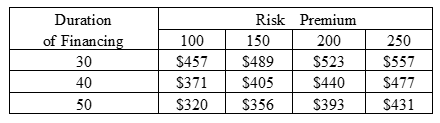

Under Indian Wells Valley’s assumptions, acquisition of Table A State Water Project (“SWP”) Contract Amounts to secure, on average, an acre-foot of imported water costs $10,560/AF ($2,112 per acre foot paid over five years). When the Mojave Water Agency acquired Table A SWP Contract Amounts to provide replenishment water, it financed its acquisition and now includes the debt service costs in its calculation of its annual replenishment rate. This reflects a common practice of water agencies—finance the acquisition cost of long-lived assets. Depending on the duration of the finance plan and interest rates, the annualized acquisition cost of Table A SWP Contract water is in the range of $300/AF (2021$) to $500/AF (2021$)—see table.

Annualized Cost Imported Water under Indian Wells Valley’s Cost Assumption,

by Duration of Financing and Risk Premium Paid over 10-Year Treasury Notes

-

- GSP Does Not Consider the Quantity of Fresh Groundwater Available in Storage or a Ramp Down Plan.

The GSA fails to consider the massive size of the basin, more than 500 square miles. A recently completed report by four independent technical teams evaluated the total useable groundwater in storage, estimating that there is more than 40 million acre-feet of fresh groundwater that can be recovered. It further estimates that pumping at current levels over the next 20 years would result in a net depletion of less than 1 percent. Water levels have dropped less than 1 foot per year historically and would cause no undesirable results within the basin over this period. The GSA fails to reconcile its strategy to prohibit a nominal amount of storage to support current beneficial uses, as required by the California Constitution Article X, section 2 and common law.

The lack of Indian Wells Valley economic reasoning is also reflected in the GSP’s lack of a ramp down of pumping to the assumed basin’s sustainable yield and withdrawal of temporary surplus.

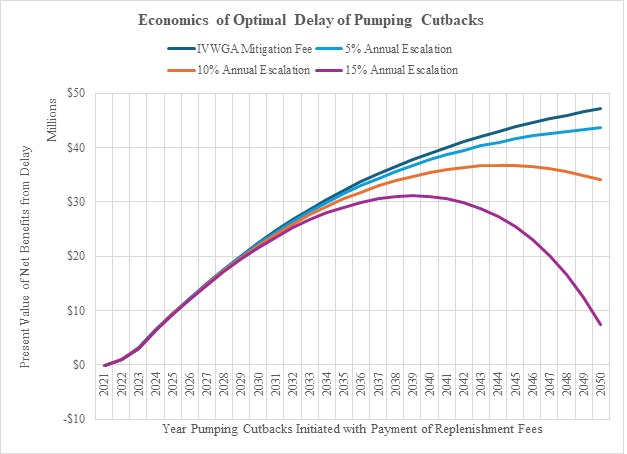

What the optimal period is to delay the initiation of pumping cutbacks with payment of replenishment fees? This requires balancing the economic value of different time profiles of allowed groundwater pumping over sustainable yield without a replenishment obligation versus the economic cost of allowing a transition period where allowed groundwater pumping exceeds sustainable yield ahead of the initiating pumping cutbacks and payment of replenishment fees for an economically viable imported water project. The GSP does not consider the question, let alone answer it.

The administrative record for the Shallow Well Mitigation Project and the economics of pistachios provides the starting point for determining a reasonable delay in imposing pumping cutbacks with payment of replenishment fees as an alternative to its proposed “Project”, which does not preserve current beneficial uses and is not designed to benefit agriculture in the first instance.

As described in Indian Wells Valley’s Engineer’s Report, “the purpose of the Mitigation Fee is to fund shallow well mitigation efforts in order to mitigate the undesirable results occurring from the basin-wide chronic lowering of groundwater levels, reduction of useable groundwater in storage, and degradation of water quality.” Discussing the plan’s revenue requirement, the Engineer Report states, “Because the anticipated damages (from groundwater overdraft) are rather linear, any reduction in the amount of the overdraft should correlate to an equal reduction in the total estimated costs; therefore the $17.50 charge should not need modification if there is less overdraft than anticipated (116,000 AF).”

While the report does not address the impact of groundwater overdrafts greater than anticipated, if anticipated damages are “rather linear” for a cumulative overdraft up to 116,000 acre feet, then the mitigation costs for overdraft above of 116,000 acre feet would also be $17.50/AF.

The optimal delay of pumping cutbacks balances the economic benefit of groundwater versus the cost of mitigation (see “Economics of Optimal Delay of Pumping Cutbacks”). The economic benefit of pumping equals the present value of Mojave Pistachio’s net revenues with groundwater through the year when pumping cutbacks are initiated with payment of replenishment fees. The mitigation costs equal the present value of mitigation costs for Mojave Pistachio’s annual groundwater pumping under four assumptions: the current mitigation cost of $17.50/AF and three assumptions about the annual rate of escalation in mitigation costs (5%, 10%, 15%). In the figure, each curve shows the difference between the present value of economic benefits and present value of mitigation costs through the year pumping cutbacks are initiated with payment of replenishment fees.

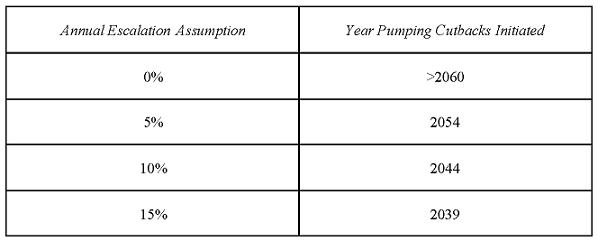

The optimal year that pumping cutbacks are initiated with payment of replenishment fees depend on the escalation assumptions (see table). Under the proposed mitigation fee without escalation, pumping cutbacks would not be initiated until after the year 2060. For annual increases of 5%, 10% and 15%, pumping cutbacks with payment of replenishment fees should start in the year 2056, year 2044 or year 2040, respectively. Given the time profile of economic benefits of delaying the initiation of pumping cutbacks, the lower the time profile of mitigation costs, the longer the optimal delay in initiating pumping cutbacks with payment of replenishment fees.

In other words, the economic management of Indian Wells Valley groundwater resources should include a significant delay in the initiation of pumping cutbacks with payment of mitigation fees. This conclusion reflects the significant economic value of groundwater use and the relatively low costs of Indian Wells Valley mitigation plan. In fact, the above analysis understates the optimal delay because the analysis did not include the value of groundwater use of other municipal, industrial, and agricultural users in Indian Wells Valley. A comprehensive analysis should also incorporate the economic stakes of these other groundwater users.

-

- Another Flaw: Conflating Stocks versus Flows

The $2,112 per acre foot component of Indian Wells Valley’s replenishment fee was calculated as the estimated acquisition cost of SWP Table A entitlements paid over five years. In effect, an acre foot of “excess” groundwater pumping in one-year is to fund the permanent acquisition of replacement water into the indefinite future. As discussed above, if Indian Wells Valley were to finance water rights acquisition costs like other water agencies, the annualized cost would be less than $500 per acre foot (2021$), or less than a third of the $1,575 per acre foot economic loss from shutting down pistachio farming. A coherent and economically literate GSP can sustain existing agriculture. Indian Wells Valley incoherent and economically illiterate GSP cannot.

Indian Wells Valley SGMA Lawfare

Indian Wells Valley used a “pay to litigate” principle to avoid addressing a substantive challenge to its GSP. By not paying the $2,130 per acre foot replenishment fee on its groundwater pumping since 2021, Mojave Pistachios lacked standing to challenge the GSP. The appellate court agreed.

Legal Double Speak

Hydrowonk discovered the legal defense “three step” years ago. First, argue the facts if they are on your side. Second, if the facts don’t help, argue the law. Third, if neither are helpful, argue procedure. Indian Wells Valley “defense” of its GSP runs directly to the third step.

Channeling the wisdom of Law and Economics, consider the consequences of the “pay to litigate” principle. In this instance, Mojave Pistachios had two options to have standing:

-

- Do not use water and go bankrupt, so one can challenge the GSP on legal and reasonableness grounds, or

- Pay the replenishment fee and challenge the GSP while incurring unsustainable economic losses hoping the legal system moves faster than the path to bankruptcy (an unlikely scenario).

Under the “litigate to pay principle”, Mojave Pistachios must sacrifice its trees upfront to challenge the validity of the GSP. In this circumstance, Indian Wells Valley faces a $112 million judgment ($80,000/acre lost value for nine-year old trees on 1,400 acres) plus accrued interest if it loses the litigation lottery.

Time Now for Common Sense?

The economically optimal management of the groundwater basin can accommodate delay before initiation of a phase-in cutbacks with replenishment obligations to fund an economically viable imported water project. Indian Wells Valley has substantial time to proceed in the development and implementation of an imported water project in an orderly and prudent manner. In fact, since Indian Wells Valley retained a team in 2019 to secure water rights for its “Groundwater Augmentation Plan,” they have entered into no definitive agreement to acquire water. If there is an urgency for action, Indian Wells Valley is not acting like it.

Instead, they have focused their efforts and spent millions on expensive engineering evaluations to import water from distant sources through a 60-mile pipeline to be constructed over open desert ground. Even assuming environmental review could be completed, and the project permitted, it is highly unlikely construction financing could be completed when there are no willing off-takers. Fearing that their scheme is unfinanceable, Indian Wells Valley has its hand out to federal taxpayers.

The delay in the optimal timing of initiation of pumping cutbacks provides the time needed to resolve the legal issues over Indian Wells Valley GSP. With judicial guidance, perhaps Indian Wells Valley may even develop coherent project and finance plans to replace its haphazard approach taken to date.

California Supreme Court Will Chart the Course for California’s Future

The California Supreme Court can clarify the ability of groundwater right owners to challenge the reasonableness of Groundwater Sustainability Plans eviscerating groundwater rights and setting of unreasonable fees and assessments. Do not let the “pay to litigate” rule provide unlimited protection of arbitrary decision-making without due process. Under the appellate court decisions, Indian Wells Valley groundwater users must enter bankruptcy to have standing to challenge Indian Wells Valley GSP. Without California Supreme Court guidance, California’s future will be one where property rights and “investment backed expectations” are relegated to the dustbin of history. Traveling this road will place water-related investment opportunities in California on equal footing with water-related investment opportunities in Bolivia.

Disclosure

In 2019, Indian Wells Valley’s legal counsel asked Hydrowonk to submit a proposal to provide advisory services regarding the acquisition of supplemental water supplies to address the area’s groundwater overdraft. The submitted response included a disciplined project plan with an emphasis on assuring that the structure of water acquisitions minimize the life-cycle costs of addressing the overdraft problem and are effectively integrated with the science underlying a Groundwater Sustainability Plan. To ensure timeliness of execution, Hydrowonk proposed a structure of retainers and success fees based on the actual acquisition of water.

This approach was not attractive to Indian Wells Valley. As they say on Wall Street and in private equity markets, “sometimes the best outcomes are the deals that don’t happen.”