In last week’s post, I wrote about how scientists at Stanford University identified approximately 2.2 billion acre-feet of water deep underground below California’s aquifers. While the “new” find that the Stanford group identified may be interesting, the economic and regulatory challenges surrounding this water supply may make it impractical for widespread use. However, are there alternatives to this water supply in California and other areas of the United States? Could similar projects be brought to bear in these areas? And if not, what are some potential alternatives to provide thirsty California with water supplies during a drought? I will address these issues in this post.

Are there places where this type of water source may be cost effective?

Two states that use substantial amounts of brackish groundwater are Florida and Texas. They use brackish groundwater mainly in coastal cities to bolster water supplies. Some regions in these states must also use these supplies out of necessity. Population growth and sea level rise have put increasing pressure on coastal aquifers in Florida and Texas. As the population expands along the coastline in these areas, freshwater groundwater levels drop and seawater replaces the areas where freshwater used to be. Sea level rise pushes salt water further inland and compounds the challenges that coastal cities in these areas must face. For example, the Florida Times-Union reports that just a one-foot rise in sea level could endanger 25% of the historic city of St. Augustine’s land mass with flooding. A group of 15 city managers in the Fort Lauderdale area say that they are already seeing more tidal flooding and saltwater intrusion into the water supplies of their communities. Fortunately for these communities, they already have some ways to use brackish groundwater.

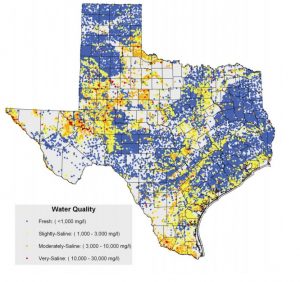

Both Florida and Texas have substantial infrastructure in place to make use of this water source. The South Florida Water Management District reports that water districts in its service area have 38 operational facilities that can treat about 270 million gallons per day of brackish groundwater, primarily through reverse osmosis. Most of the treatment plants in Florida are along the ocean to help relieve stress on freshwater supplies that saltwater intrusion threatens. As of 2015, the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB) reports that 46 municipal brackish water desalination facilities can produce up to 123 million gallons per day. Forty-four of the 46 plants use reverse osmosis technology. In the Lone Star State however, areas of brackish groundwater are not just along the coast (see graphic below). TWDB estimates that Texas has approximately 2.7 billion acre-feet of brackish water supplies across the state and in a range of salinities. Major cities are also tapping into this previously unused resource. The San Antonio Water System is building a three-phase, $411 million brackish groundwater desalination project that will provide the city with approximately 33,600 acre-feet of water when the plants are ultimately completed in 2026. Initial projections estimate that San Antonio will pay approximately $1,100 an acre foot for this desalinated supply. It is likely not as expensive as potential sources from some parts of California because the brackish groundwater below San Antonio is not as deep. The Lower Wilcox Aquifer from which the project will draw its supplies begins at about 950 feet below ground, so the electricity costs associated with pumping the water out will be lower than if California operators were to pull water from thousands of feet below the surface.

There are some places in California where end users may someday use brackish groundwater desalination. In the Pajaro Valley along the Pacific coast between Monterey and Santa Cruz, decades of groundwater pumping and the lingering effects of the drought have brought the water level in some areas of the groundwater basin below sea level. Initial research from the State Department of Water Resources confirms that saltwater has migrated up to 6 miles inland in parts of the valley, and DWR designated the basin one of 21 in the state in critical overdraft. In response, local water districts have teamed together to build a recycled water delivery system that sends wastewater to these critical areas to act as a buffer between the salt and freshwater supplies. While these programs can protect against further saltwater intrusion, it cannot undo the damage that saltwater intrusion has already caused to the basin. As such, this area and other areas along the California coast that saltwater intrusion threaten may be able to use desalination technologies to make the most of the water supplies they have. As the Journal of Water reported in February 2016, the Castroville Community Services District (CCSD) in the Salinas Valley plans to partner with the California American Water Company (Cal-Am) to provide desalinated water to the community of Castroville. Under the terms of the agreement, Cal-Am would provide up to 800 acre-feet of desalinated water to CCSD in lieu of pumping groundwater. Additional water supplies may also go towards the Castroville Seawater Intrusion Program (CSIP) which gives groundwater users recycled water instead of pumping to reduce stress on the aquifer. These programs show successful uses of brackish and desalinated groundwater in California and the greater US. However, these programs do not involve the pumping of deep groundwater, and I do not believe that deep groundwater desalination projects will find much traction in the near future.

Alternatives for California

While there may be some limited use of deep groundwater supplies in California, economic and regulatory hurdles likely will limit its widespread use across the state. Unfortunately, barring a rainy upcoming winter, California will enter into its 6th year of drought. Water supplies will continue to be limited (for example, the San Luis Reservoir, a key federal and state facility currently sits at just 15% full, 20% of its historical average according to the California Data Exchange Center) and Californians will have to keep using water wisely. There are more practical and cost effective ways to meet that goal. First, water conservation for all users must remain a priority. Last year, Governor Jerry Brown enacted statewide mandatory water use reductions, and the vast majority of communities were able to meet their reduction targets. However, as of June 2016, the state no longer imposed mandatory restrictions and water savings started to taper off. The State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) reported that statewide water conservation only reached 21.5% in June 2016 versus 28% in May and 27.5% in June 2015. State water officials will look to see if this downward trend continues or stabilizes. Felicia Marcus, Chairwoman of the Board said, “Is the drop a trend and it’s going to keep going, or is it an appropriate readjustment given where we find ourselves? Relaxation is OK. We are just worried about it plummeting.” An article in the Christian Science Monitor interpreted the new data differently: They argue that the conservation measures enacted last year represent new habits and a way of thinking, and as a result the public may not immediately revert to the old habits of using more water.

While it is debatable whether Californians need the “stick” of mandatory conservation laws, it is clear that the state can conserve water when pushed to do so. Conservation is also an efficient way to manage our water resources effectively. When we conserve water, no money needs to be spent on pipelines, reservoirs or dams. But conservation can only be one piece of the water management puzzle. Other cost-effective water resources have to be brought to bear, and there are better alternatives than deep groundwater extraction. The increased use of recycled water for example in many instances can provide a reliable and more cost-effective option for water supplies. For example, the Journal of Water reports that the City of Turlock reached a 40-year agreement to provide about 7,900 acre-feet of water per year to the Del Puerto Water District. Del Puerto Water District is a Central Valley Project contractor, and this year, the US Bureau of Reclamation is only providing 5% of the total contract amount to contractors south of the Delta such as Del Puerto. Recycled water can provide a constant, reliable and in some instances cheaper alternative to variable water rights contracts such as those from the Central Valley Project. Alternatives such as these should be pursued before we look to more costly and impractical supply sources.

California and many other western states will have to make tough decisions regarding their water supplies as drought and climate change continue to affect the region. In my opinion, in the context of the recent deep aquifer “water finds,” there is both good news and bad news for the region’s water supplies. First the bad news – unfortunately, the deep groundwater supplies that the team at Stanford identified likely are not cost effective to extract and would run into a few regulatory hurdles that make using this water supply challenging. The good news is that Californians have proven that they can conserve water when they need to. Further, regions across California have the ability to increase the use of recycled water and storm water capture to provide alternative supply options to the state’s water portfolio. California should focus on these water resources before we consider even thinking about how we may be able to use deep groundwater supplies.