What is missing from the map of the United States right now? Well in general, drought is missing. According to a recent US Drought Monitor, the contiguous United States had the lowest reading of overall drought in the 17 year history of the weekly service. For the week of May 2nd, only 4.98% of the contiguous US had some form of drought. According to the USA Today, the lowest prior reading for the US was 7.7% of the US in drought, set in July 2010. It also compares favorably to a record high of 65.5% of the US in some form of drought set in September 2012.

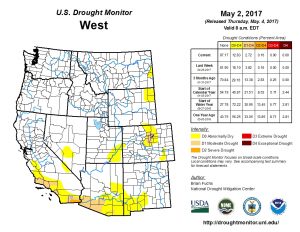

Even more amazing is the general absence of drought in the western United States. During the first week of May, only 2.72% of the western US has drought conditions (see image below). No extreme or exceptional drought remains, and only small portions of southeastern California and southwestern Arizona along the Mexican border have severe drought. The states of Washington, Oregon and Idaho are completely drought free. As I wrote in a 2016 Hydrowonk post, the Pacific Northwest dealt with similar drought conditions as California for the last few years, so the turnaround has been incredible.

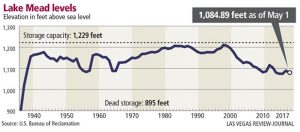

While both rainfall and a generous snowpack across much of the western United States (California skiers rejoice – for the first time in history, the Squaw Valley Ski Resort by Lake Tahoe does not plan to close this summer) will provide ample water supplies, the longer-term picture about water supplies in the western US is much less clear. Unfortunately, the rain and snow has not completely erased the effects of the drought. Lake Mead for example at the end of April sat at 1084.89 feet, over 100 feet below full capacity. So while the drought may have abated in the western US, the Colorado River Basin States and Mexico will have to plan for drought contingencies in the future. But the multi-agency and binational effort to conserve water on the Colorado River has not reached the broad-based agreement that many stakeholders wished that they would have reached by now. In this post, I will look at the proposed multi-state Drought Contingency Plan, explore the implications of the proposal should the Lower Basin States come to an agreement on terms and explain why this agreement has not yet been finalized. In my next post, I will look at Minute 32x, an amendment to an agreement between the United States and Mexico regarding the two countries’ allotments of the Colorado River. I will explore the goals that these two agreements aim to meet and the potential implications if they are not signed.

Colorado River Drought Contingency Plan

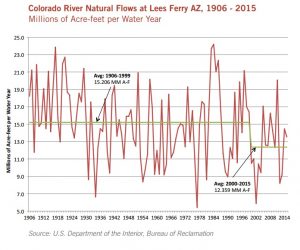

As the chart above shows, storage levels at Lake Mead have been in general decline since the late 1990s. Population growth in cities that rely on the River as well as agricultural demands and periods of sustained drought have put pressure on the river’s supply. Furthermore, the period beginning in the year 2000 saw significantly lower natural river flows than the prior 90 years. According to the Colorado Foundation for Water Education, the river had an average annual natural flow of 15.206 million acre-feet from 1906-1999 measured at Lees Ferry, AZ. From 2000 to 2015, the natural flow measured at the same point averaged 12.359 million acre-feet annually. By the mid-2000s, it was increasingly clear that storage levels at Lake Mead were on an unsustainable path. In 2007, after two years of negotiations, the seven Colorado Basin States agreed to the Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages . This agreement established guidelines for the Secretary of the Interior to manage the Lower Basin water supplies including:

- Determining the circumstances under which the Secretary of the Interior would reduce water available for consumptive uses from Lake Mead to the Lower Basin States

- Establish guidelines for the coordinated operation between Lake Powell and Lake Mead to improve operations in each reservoir, particularly in drought conditions

- Establish guidelines that would allow conserved Colorado River water and non-system water to be stored in Lake Mead to increase operational flexibility, create a drought buffer and increase flexibility of meeting water use needs during times of drought

- Determine the conditions under which the Secretary of the Interior can declare the availability of surplus water for Lower Basin states

But even these guidelines did not slow the rate of elevation decrease in Lake Mead. In addition, much of the western United States entered into varying degrees of extreme drought starting in earnest in 2012. According to the US Drought Monitor, the western United States had at least 50% of the land mass with some form of drought for parts of each year between 2012 and 2016. The Interim Guidelines also set up the parameters of how water shortages would be addressed in the Lower Basin States. Not all water rights are created equally – there are both “senior” and “junior” water rights. California for example holds water rights to the Colorado River that are senior to Arizona’s water rights. As I addressed in a series of Hyrdowonk posts, the US Bureau of Reclamation could declare a water shortage, and Arizona’s water supplies would be the first to feel the pinch. The shortage measures will go into effect if the Bureau of Reclamation’s August 24-Month Study forecasts that the level of Lake Mead as of January 1 of the following year is below 1075 feet. As the threat of cutbacks loom, Arizona has tried to work with the other Lower Basin States to hash out a more comprehensive Basin management program.

Since 2015, the Lower Basin states have been negotiating the Drought Contingency Plan, an agreement that would see Arizona and Nevada voluntarily accept deeper cuts to its supply if California agrees to cuts equivalent to 5-8% of its water supply. The prolonged drought across the western US coupled with the very real possibility that the US Bureau of Reclamation could declare a drought emergency pushed states that usually settle arguments with attorneys in court to the negotiating table. Metropolitan Water District of Southern California CEO Jeff Kightlinger said of the negotiations that they would be “unthinkable” a decade ago, and added, “We realize if we model the future and we build in climate change, we could be in a world of hurt if we do nothing.” However, the Drought Contingency Plan is facing hurdles and has not yet been executed.

The transition between presidential administrations is causing policy uncertainty among the Lower Basin States looking to negotiate the deal. The US Department of the Interior is the lead federal agency for the negotiations associated with the Drought Contingency Plan as well as the negotiations with Mexico regarding Minute 32x. According to the Las Vegas Sun, outgoing Interior Secretary Sally Jewell told her staff to continue working with the states on the plan. Incoming Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke was confirmed by a 68-31 vote on March 1st, but Chris Harris, executive director of the Colorado River Board of California said, “We are sort of on a hiatus.”

Beyond the change in administration, there are still some key areas of the negotiations that have to be hammered out. At the 2016 Colorado River Water Users Association (CRWUA) annual conference, two influential water users in California, Imperial Irrigation District (IID) and Metropolitan Water District of Southern California expressed reservations about supporting the plan. The Journal of Water reports that the Imperial Irrigation district’s primary concern relates to the Salton Sea restoration. As fellow blogger Rod Smith confirmed in his site visit to the Salton Sea in March, the elevation of the Salton Sea has dropped by almost 8 feet since the late-1990s, exposing miles of shoreline. The dust from the exposed shoreline could cause more toxic dust to swirl up from the site, potentially affecting parts of Southern California and Arizona. Further, as part of the water transfer between IID and San Diego County Water Authority (SDCWA), IID had to provide mitigation water to the Salton Sea to make up for the lower amount of runoff going to the sea from reduced agricultural operations. IID’s obligation to provide mitigation water to the Salton Sea ends this year. Because of IID’s concerns about the environmental impacts of a further exposed Salton Sea, IID General Manager Kevin Kelley said, “If there is no going forward at the Salton Sea, then IID cannot help at Lake Mead.”

Metropolitan Water District also has reservations about moving forward with the plan. During the drought, water supplies from Northern California became increasingly unreliable. In 2014 for example, the State Water Project delivered 5% of contracted supplies, a historically low amount. In a 100% delivery year, Metropolitan has 1,911,500 acre-feet of supply, but in 2014, it only received 95,575 acre-feet. Meanwhile, the citizens of the greater Los Angeles area still required water, and as such, the District relied on its Colorado River supplies for a greater percentage of its overall water portfolio. The District’s reliance on the Colorado River as a drought buffer and the uncertain future of northern California water supplies are playing a role in their reservations to support the Plan. At the CRWUA conference, Metropolitan General Manager Jeffrey Kightlinger said that without a more certain water supply picture from the Bay-Delta, his agency would find it hard to support the Contingency Plan.

Short-Term vs. Long-Term Planning

MWD Colorado River Resources Director Bill Hasencamp put the challenges associated with Colorado River water supply succinctly when he said, “Lake Mead is like going to Vegas. You might win a couple of times. You might even hit the jackpot. But in the end, the odds are stacked against you.” This winter, the weather has brought a “jackpot” of snow and rainfall across the Colorado River Basin. The wet winter and the bounty of water supply will buy the Basin States some time in coming to an agreement on how to manage the Colorado River sustainably. However, the rainfall does not fix the structural deficit that the users of the river continually put on the river’s supplies. Further, it is clear that the negotiations surrounding the Drought Contingency plan are complicated and require the buy-in from a host of interests. Issues such as the Salton Sea restoration or the challenges in the Bay-Delta will not be solved overnight. However, the states that are parties to the Contingency Plan will have to come to an agreement on water usage reductions, or Mother Nature will force their hand in the next drought.